Literacy embedding in post-16 education – undressing the L word

Back

Literacy embedding is a somewhat ghostly policy. It has lurked around for decades, variously in and out of favour; since the demise of Skills for Life in 2011, it has been frustratingly absent from the policy space. We all understand the importance of embedding literacy in subject content, especially for colleges in deprived areas, and particularly now with the arrival of T Levels. But there are unresolved questions. What does effective literacy embedding look like in KS5 subjects? How can in-service teacher training support embedding, and what does the ‘L word’ actually mean?

These are questions I’ve been grappling with for twenty years. As an English teacher, college Literacy Lead and PhD student, I’m all too aware of the disconnect between practice, policy, and research. This lack of consensus has, in my view, produced blurred understandings of the core question – what is post-16 subject-literacy? Literacy is a deceptively slippery concept. To pin it down, let’s look at an example of embedding in practice.

Literacy embedding in BTEC Sport

Imagine an urban college classroom. Sam is preparing her students for a coursework assignment about the impact of psychology on sport performance. In previous years, she’s focused most of her contact time chalk-&-talk teaching the core content – the ‘know-that’ elements of the curriculum, primarily assessed by the Pass criteria. But students struggle with the more demanding analysis – the ‘know-how’ of breaking down the factors and examining how and why they interrelate. Sam knows that without significant support, there will be few Distinctions.

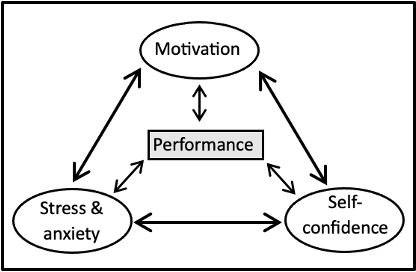

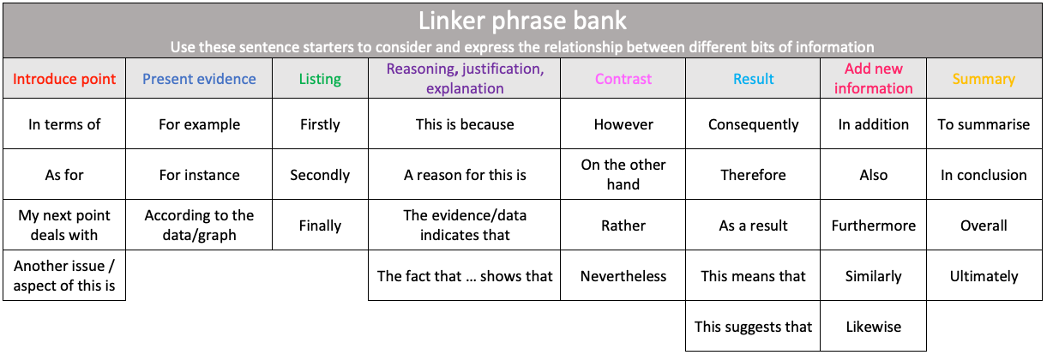

This year, she takes a different approach. She starts by preparing a graphic organiser that represents the relationships between three psychological factors and performance. She also finds various text and media sources which cover the content. Dealing with one factor first, students scan-read the text for key Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary, matching them to definitions. Next, they watch Sam model how to identify and paraphrase core concepts from the text, and then do the same, making notes into the graphic organiser. Sam then gives a mini-lecture about the impact of motivation on performance. Whilst listening to this oral model, students use a linker phrase bank (see below), highlighting the phrases they hear Sam use. They then use the phrases to fill the gaps in a short model analysis text, after which pairs use the bank to discuss the relationship between the factors in more detail. In subsequent lessons, Sam repeats these steps with the remaining factors, interleaving the content (know-that) and analysis (know-how). Students synthesise information from the various sources, gradually building their knowledge, all the while adding to the graphic organiser.

This year, she takes a different approach. She starts by preparing a graphic organiser that represents the relationships between three psychological factors and performance. She also finds various text and media sources which cover the content. Dealing with one factor first, students scan-read the text for key Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary, matching them to definitions. Next, they watch Sam model how to identify and paraphrase core concepts from the text, and then do the same, making notes into the graphic organiser. Sam then gives a mini-lecture about the impact of motivation on performance. Whilst listening to this oral model, students use a linker phrase bank (see below), highlighting the phrases they hear Sam use. They then use the phrases to fill the gaps in a short model analysis text, after which pairs use the bank to discuss the relationship between the factors in more detail. In subsequent lessons, Sam repeats these steps with the remaining factors, interleaving the content (know-that) and analysis (know-how). Students synthesise information from the various sources, gradually building their knowledge, all the while adding to the graphic organiser.

The students have now completed the first stages of the writing process – they’ve collected information, clustered it under headings, and understand the ‘how’ and ‘why’ interrelationships. It’s now time to plan the text structure. After paraphrasing the task brief, students use the graphic organiser to discuss the most logical way to structure the information. Sam then provides or elicits a list of sub-headings which students put in order, justifying their choices. Once the plan is ready, she leads a collaborative writing session, eliciting, sentence-by-sentence, a model introduction. Noting the function of each sentence, she models the process of editing and SPaG proofreading. The students are now ready to draft their assignments independently.

What is post-16 subject-literacy?

Sam’s example demonstrates multiple understandings of literacy. At the very surface is spelling, punctuation and grammar. Although SPaG is considered a common synonym for literacy, it’s a mere drop in the ocean. Deeper currents swirl beneath. At the core of the assignment is its ‘analyse’ function, since the cause-effect dynamic dictates the shape of the final text as well as its language structures. The focus on linker phrases is a crucial part of teaching ‘analyse’. Because we do this type of thinking in language, a ready handle on the phrases promotes more precise thinking. This is why Sam incorporates oracy. Getting students to use the linker phrases in structured dialogue pushes them to get their mouths and minds around the language, deepens their analytical understandings, and rehearses for writing.

A related dimension of literacy is the reading and writing processes. Sam understands that collecting, organising, and categorising information are the first steps of the writing process. This is why she sets up the graphic organiser from the get-go. This maps out the structure of the information - it represents the relational knowledge, and models an approach that students will eventually use independently. Sam’s subsequent activities teach the latter steps of the writing process - text planning, introduction writing and editing-proofreading. She deals with reading processes in a similar way. By modelling the processes of scanning, dealing with unfamiliar vocabulary, and extracting core concepts, she’s doing two things: teaching the content know-that, and developing the know-how to deal with academic texts. Her goals are oriented towards the present task in-hand, and the students’ future progression to higher education.

What should we do about the ghost of embedding past?

My intention here is to demonstrate that subject-literacy is inseparable from subject content knowledge. They’re bound together in the same curriculum package. In fact, I’d go further to say that subject-literacy is subject know-how. Sam clearly has this understanding – the fact that she no longer sees literacy as a bolt-on communication skill enables her to develop the embedding practices described above.

So, what are the policy implications of this? In my view, if we’re committed to narrowing the socio-economic attainment gap, which is at its widest post-16, we need to develop strategies to foster better understandings of literacy and embedding. Rather than resurrecting the ghost of embedding past, I suggest that we reconsider what we mean when we say ‘literacy’. Maybe then we can join Sam in providing an education which genuinely does as it intends.

Rose Veitch is a PhD research student at King’s College London. Her research focuses on literacy embedding and in-service teacher learning. If you have any comments or questions, please email her.