An idea for managing this year’s unreasonable appeals process

Back

Well, the TAGs have now been submitted. And what a lot of work that was. It would be comforting to think that the effort associated with this year’s grades is now over, but many of us fear that it isn’t. As we all know, teachers are in the front line for appeals, and so it’s very likely that those phones will be ringing, and those email inboxes overflowing, as soon as the results are announced on 10 August.

We all respect the right of students, parents and guardians to appeal, but the possibility of being overwhelmed is real, and some of those interactions can be disagreeable, to say the least.

One of the problems, of course, is that appellants are unlikely to have studied clauses GQAA4.1(a)(ii) and GQAA4.1(b)(ii) of the General Qualifications Alternative Awarding Framework as published by Ofqual on 8 June 2021, and so might be unfamiliar with the specific meanings of the terms “administrative error” and “unreasonable exercise of academic judgement”. I’ll make a suggestion as to how that problem might be addressed shortly; but let me dwell for a moment on those words “unreasonable exercise of academic judgement”.

My understanding of those words is that an appealed TAG will be changed only if the exam board considers that the academic judgement used to determine that TAG was “unreasonable”. Which is good news for teachers for this is, I think, very difficult for an exam board to do. In practice, this is likely to mean that the great majority of originally-awarded TAGs will be confirmed rather than over-ruled. But the process by which this will happen will be time-consuming and irksome indeed – and, from the appellant’s standpoint upsetting and nerve-wracking, especially if that much-sought-after up-grade were to open a door that is otherwise firmly shut. And when an appeal fails, the appellant is exhausted, distraught, angry, bitter.

At first sight, this policy might appear to be “reasonable”. But is it?

In essence, this policy denies access to a second opinion unless the first opinion can be proven to be “unreasonable”. For an appellant, this sets the bar very high, and much higher than in other professional contexts such as medicine and the law. Consider, for example, a court judgement. Yes, there was a jury. Yes, there was a judge. Yes, there was a defence lawyer. The process was followed to the letter. There were no “administrative errors”. And no, the judge’s verdict was not unreasonable. Imagine the outrage if that were to deny the right to appeal. Yet this is exactly the position as regards exams.

In all matters involving professional judgement, what an appellant seeks is an expert second opinion. That’s not to imply that the first opinion was ‘wrong’; rather, it recognises that a second, equally expert, opinion might be different, for that’s what professional opinions are all about. And if that second opinion is in the appellant’s favour, and equally valid, then why not?

All exam results are based on marks, and those marks are professional opinions which may differ, as indeed is recognised by Ofqual, who acknowledge that “it is possible for two examiners to give different but appropriate marks to the same answer. There is nothing wrong or unusual about that”. This has profound implications as regards the (un)reliability of exam grades, and as discussed in another Blog 6, explains why those grades are only “reliable to one grade either way”. It is also central to the appeals process, for it admits the possibility that a second opinion, in the form of a fair re-mark, might result in an up-grade. And this year, professional opinions are of wider scope than just marks, but apply to the protocols too.

But Ofqual refuse to allow access to second opinions.

This refusal is quite recent, for a re-mark used to be allowed on request. But in 2016, Ofqual changed their rules, making it harder to appeal and explicitly denying access to a second opinion, which they disparagingly dismissed as “an unfair second bite of the cherry”. It’s worth looking at Ofqual’s documents of that time, for they are, to my mind, classics of bureaucratic double-speak. But that obfuscation and convoluted ‘reasoning’ had a very deliberate intent. To block appeals. Which, when you think about it, is a strange thing for a regulator to do. Surely, the regulator is there to protect students’ interests? So why make it harder to appeal a grade?

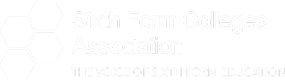

There is an answer. Appeals are Ofqual’s nightmare, especially appeals judged in favour of the appellant, appeals in which that second opinion re-mark results in an up-grade. For each up-grade is a demonstration of Ofqual’s failure to do its job. And something “interesting” was happening in the years from about 2009 to 2015. The number of A level, AS and GCSE awards was in general going down, following the demographic. But every year the number of appeals was going up, as was the number of up-grades. Which, when you think about it, is odd. You’d expect the number of up-grades to run more or less in line with the number of awards. But that was not what was happening. Maybe markers were getting progressively sloppier? Well, if that’s the case, we’d better improve the quality of marking – which you might recognise as one of Ofqual’s mantras. They tried that in the early 2010s. But it didn’t work. The number of up-grades just kept on rising…

From Ofqual’s standpoint, this was bad news. So one way to stop grades being changed on appeal is to declare that no longer would appellants be allowed a second opinion. Hence the change in the rules in 2016. And that change ‘worked’. From 2016 to 2019, the number of appeals, and up-grades, stabilised:

Up-grades in England, 2009-2019 as % of total of grades awarded

Sources: Ofqual’s official statistics for 2009 – 2010, 2011 – 2014 and 2015 – 2019.

The data for 2014 – 2019 (blue squares) are Ofqual’s; those for 2009 – 2013 (blue circles) are my estimates, based on adjusting Ofqual’s 2009 – 2013 aggregate data for England, Wales and Northern Ireland for the average contributions to the overall total made by Wales and Northern Ireland over 2014 – 2017, as reported here. The red line is my extrapolation of 2009 – 2015.

That’s why Ofqual is using the “unreasonable academic judgement” rule. It’s not to protect teachers. It’s to protect themselves.

This year, teachers will certainly be beneficiaries of this rule, but this is an “unintended consequence” of a longer-term, deeper, policy. With which you may, or may not, agree. And almost certainly a policy that your students, and their parents and guardians, won’t know about.

So, back to this summer, and the very sensible need to ‘manage’ the appeals process. Which leads me, if I may, to a suggestion. Suppose each college were to write to each student’s parents or guardians, so that they are well-informed on the appeals process. Such a letter could include, for example, a statement about the care that has been taken to determine this year’s TAGs, and the integrity of the process; it could then continue to outline the key rules for appeals – explaining the allowed grounds based on “administrative errors” and “unreasonable academic judgement”. And there is also an opportunity to state that the college’s hands are tied as regards any appeal to a second opinion, and that should a second opinion be sought, then the appellant should contact Ofqual directly. Perhaps even with the college’s support. Maybe it shouldn’t be just teachers’ email inboxes that should overflow…

Dennis Sherwood runs Silver Bullet Machine, a boutique consultancy firm, and is an education campaigner.